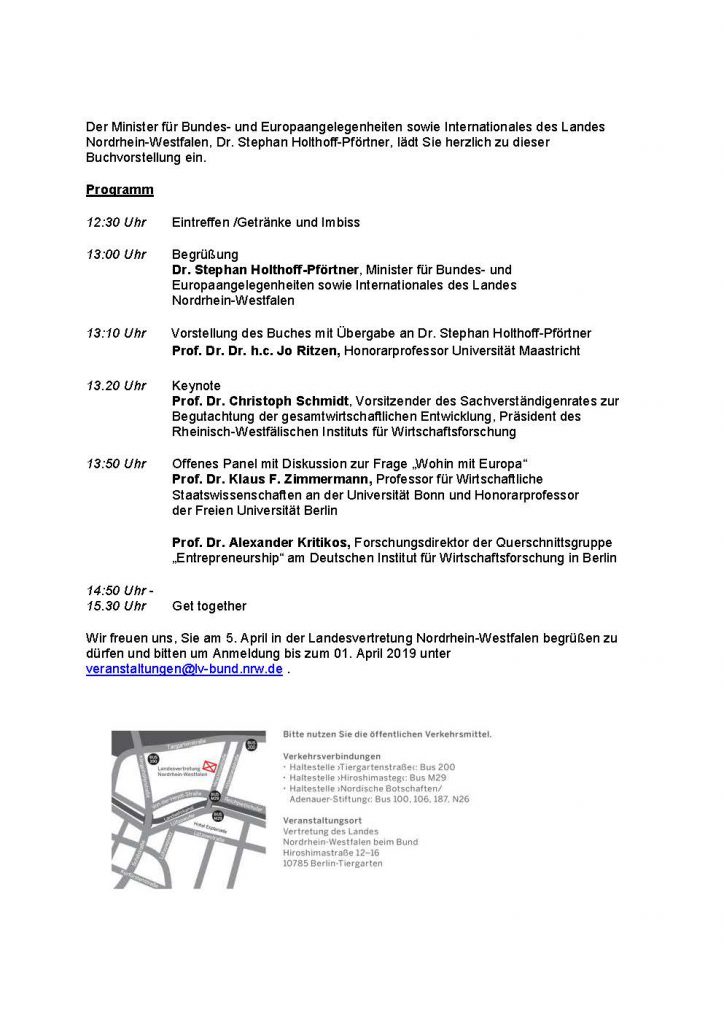

The Berlin Government Office (Landesvertretung) of the State of North Rhine – Westphalia hosted on Friday April 5 the launch of the German book of ‘A Second chance for Europe: Economic, Political and Legal Perspectives of the European Union’ presented by Jo Ritzen. (“Eine zweite Chance für Europa: Wirtschaftliche, politische und rechtliche Perspektiven der Europäischen Union. Königshausen & Neumann). The host, Stephan Holthoff-Pförtner, Minister of North Rhine – Westphalia in Berlin, introduced the event, and Christoph Schmidt, President of the RWI Leibniz Institute for Economic Research and Head of the German Council of Economic Experts, provided a keynote speech discussing the challenges of Europe and evaluated the solutions outlined in the book. The detailed agenda can be found here.

Author Jo Ritzen, who is a former Dutch Minister of Education, a former Vice-President of the World Bank and the Past-President of Maastricht University, and has been a Professor of Economics before his remarkable career in politics, is currently working as Honorary Professor of Maastricht University and Fellow of the Global Labor Organization (GLO). At the book launch, he was presenting the major contributions of the book, which is based on joint research with a number of GLO Fellows.

Also present and serving in a panel discussion after the book presentation were Alexander Kritikos, Research Director of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), Professor at the University of Potsdam and GLO Fellow, and GLO President Klaus F. Zimmermann, currently visiting the Central European University (CEU) in Budapest as the George Soros Chair Professor. Zimmermann is also co-author of two chapters in the book.

In the view of Ritzen, key challenges for Europe are (i) the social market economy, (ii) governance including corruption, (iii) internal and external labor mobility, (iv) the asylum issue, (v) the dept crisis and the Euro, and (vi) the knowledge society. It was common sense among the speakers that more Europe and not less is needed in the future to manage the current and forthcoming challenges.

Latest news: The next version, Jo Ritzen announced at the meeting, will be in Spanish.

Budapest, early morning. Zimmermann leaves for Berlin.

Private jet, easy.

Stephan Holthoff-Pförtner,

Christoph Schmidt

Ends;